A goal to improving medication access is to help patients without insurance become eligible for charitable pharmacy services. This may involve providing medication directly, enrolling patients in a manufacturer patient assistance or bulk program, or directing them to a mail-order or other discount program. There are transitions of care involved. Frequently special services are required such as translation, interpretation, dealing with illiteracy, arrangements for homeless or those who have been incarcerated. The charitable pharmacy is in a unique position to address these needs and create reasonable options for their patients.

For patients to receive medications at the pharmacy, recordkeeping measures for eligibility and required documentation should be in place. Records need to be securely stored according to state and federal guidelines (e.g. Adults: 7 years; Under 18, 7 years past 18th birthday.) Records may be stored as paper or electronically depending on state and federal guidelines.

Case Management or Discharge Planning Team identifies that patient is uninsured and may have difficulty filling their prescriptions

Patient is eligible for Dispensary of Hope (DOH) meds,

IF 1) UNINSURED (pharmaceutically uninsured)

AND 2) < 200% FPL

*If possible, document patient eligibility in EMR for patient to be pre-qualified when they arrive at the pharmacy

Prescriptions may be filled and delivered to patient’s bedside (if med-to-bed program is in place), OR direct the patient to the hospital’s outpatient pharmacy that has a free inventory, OR local Charitable pharmacy. The pharmacy will try to fill as many Rxs at $0 that are available in the pharmacy.

If the patient is not eligible for DOH or free meds OR if some meds are not available in inventory, THEN see if one of the following strategies will work to obtain affordable medication access

THEN

If possible, make therapeutic interchange to med that is available for free

If not, THEN

Use manufacturer drug card

Sign the patient up for Patient Assistance if applicable

If not, THEN

Use the 340B drug price if hospital is 340B eligible

If not, THEN

Use a limited safety net formulary where certain medications are only $1 or $3 for the patient price to fill any gaps

If not, THEN

Use a Rx discount card (i.e. Family Wize, GoodRx)

If not, THEN

If the hospital has a charity fund, then fill any remaining Rxs out of this fund

Adapted from Dispensary of Hope Flowchart for external referral

Key elements to determine when developing eligibility guidelines include demographics of the population being served and any guidelines from referral sources, funders, vendors or state drug donation programs. Work with referral sources (case management, etc.) to determine how they track and determine eligibility. When possible, utilize pharmacy point of service software to check patient insurance status.

Develop criteria for patients to meet to receive new and refill medications. Criteria can include:

- Household income

- Income usually includes that of entire household, not just patient

- Size of household: adults, children under 18

- Program criteria may vary: Children over 18 may not be counted as part of household by some programs

- Romantic partner may count but someone just staying may not

- Difference in household income versus expenses

- Where patient resides: zip code, city, state

- Patient age

- Provider network or referral source

- United States residency status

- Veteran

- Eligibility for other assistance programs (social security, disability, state, etc.)

- Prescription drug insurance status: uninsured, gap in insurance, donut hole, spend down, etc.

Do these guidelines fit the demographics of the patient population to be served?

Do these guidelines fit the eligibility requirements of the medication suppliers used? (Manufacturer bulk replacement, patient assistance programs, non-profit vendors, purchased distributors, state drug donation program, etc.)

Some vendors require all documentation to be acquired prior to dispensing of any medication, even first fill.

Acceptable proof of eligibility and guidelines for documentation.

Photo ID. Exceptions: discharge from a facility, mail order, patient not able to be present (age, illness, disability), minors

- Types of acceptable photo ID: State/government-issued, school-issued, credit/debit card, other

- Residency: USPS mail, utility bill, rent receipt, or copy of lease

- Residency, others: homeless, shelters, rehabilitation center, facility, staying with another person: See appendices form letter.

- Insurance: denial letter, lack of coverage criteria (not US resident, etc.), attestation

- Some software programs can screen for prescription insurance status

- Income: pay stubs (how recent, how many?), bank statement, letter from employer (notarized may be burdensome for patient), attestation, Social Security, child support, previous year tax form

- For those paid in cash, sample letter for income documentation is in the Appendices. A phone number of employer may be added. This may not be acceptable for manufacturer PAPs.

- A formalized letter of support from family members, friends, organizations that help support the patient’s bills may be required.

- Are food stamps considered income in your state, for eligibility for meds from the vendor or manufacturer program?

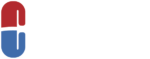

Example Algorithm for acceptable income documentation:

Determine timeline for patient to provide documents needed for initial eligibility

- Prior to dispensing

- Prior to refill, 30 days, 60 days, 90 days

- Exceptions: emergency medication, other

Criteria for refill

- All documentation provided

- For mail order, 10 business days prior to refill needed. This may be adjusted for shipping holidays and delays (weather, etc.)

Criteria for 90-day supply refill versus 30 or 60-day fill

- Some pharmacies restrict all refills to 30-day supply to monitor adherence

- Another option is monitoring patient 30-day refills. When 3 refills in a row are timely (+ or – 3 days of due date), the patient is congratulated for adherence, a note made in patient chart, and future refills will be for 90 days. This may require a collaborative practice agreement in some states.

- For shipping of maintenance meds, a 90-day supply following first fill may be set as a policy for the program.

Allow for extra time for new patient enrollment (30-60 minutes) and re-enrollment (10-15 minutes). Patient enrollment processes may vary based on suppliers of medication (vendor requirements, prescriptions being filled in-house or via PAPs) and software systems being used.

TIP: Collaborate with referral sources to complete eligibility form or include a demographic sheet including income and insurance coverage. This decreases duplication for patients and allows the pharmacy staff to concentrate more on medication and medication related services.

- Develop method of enrollment:

- Form(s), paper chart

- Electronic: pharmacy system or another system. Software for enrollment and/or PAPs may be separate than that used for prescriptions.

- Alert for missing documentation

- System should be capable of providing metrics for patient demographics including but not limited to age, sex, language and/or ethnicity, income, insurance status, referral source, location, and contact information. (See Chapter on Measurements/ Evaluation/Outcome for more information.)

- HIPAA/Privacy form(s) for (original) patient signatures

- Possible exceptions for original signature

- Discharge from facility, minor, patient unable to be present (age, illness, etc.), other

- Give copy to caregiver to return(?)

- Possible exceptions for original signature

- When using state drug donation medication, a liability protection for both donors and recipients form is signed by patient (bottom of page).

- All forms and patient materials may need to be translated into multiple languages depending on the population being served. Interpretive services are discussed below. . An interpreter may be needed to ensure patient understands what documentation is needed for enrollment

- Some patients may not read and may require oral completion of forms.

- Determine re-enrollment period and criteria

- Semi-annual or annual

- All new proofs of eligibility or limited (income, residency, insurance, etc.)

- Alerts for re-enrollment

Example: Patient enrollment forms can be found in Appendix/Eligibility.

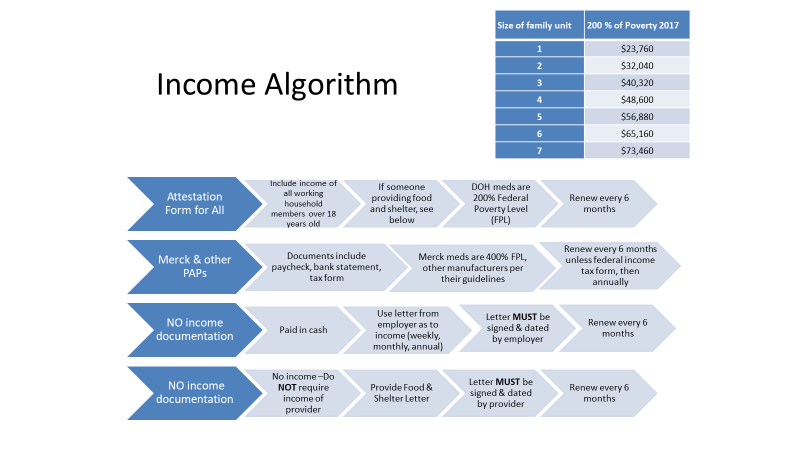

Example: Algorithm when information is lacking

When a medication is not available at your pharmacy, options include:

- Changing medication to a therapeutically equivalent medication carried

- Referring to a discount pharmacy for a $4 or discounted med or equivalent

- Providing a manufacturer coupon

- Checking with a specialty provider who may have access to medication until supply is available

- Referring to another outreach provider (Rx OutReach, Xubex, GoodPill, Honeybee Health or a community- based provider)

- Enrollmentin manufacturer Patient Assistance Program

See more details in Filling Gaps in Free Medication

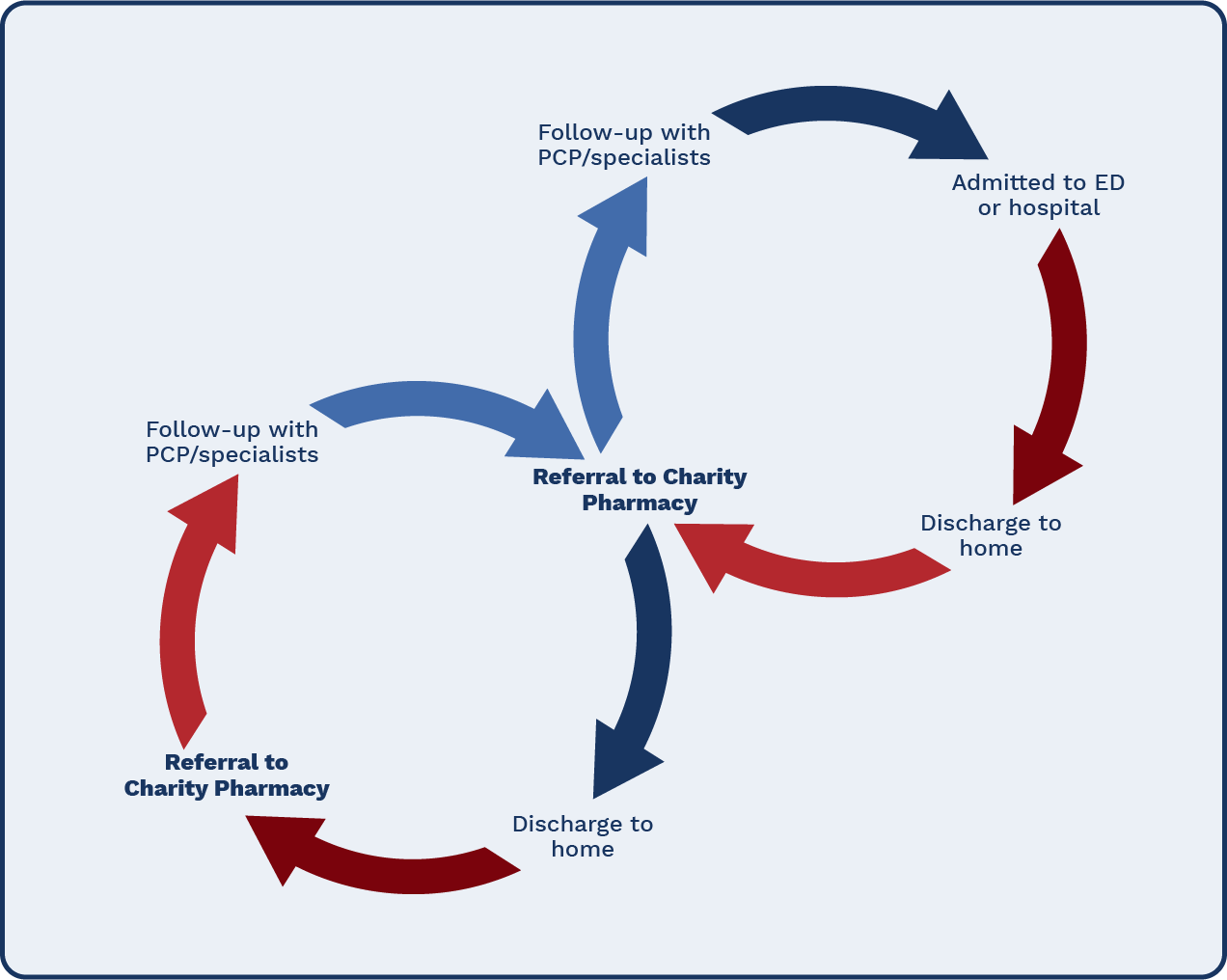

An important service required of pharmacies is assistance in transitions of care (TOC). The National Transitions of Care Coalition defines transitions of care (TOC) as “the movement of patients between health care locations, providers, or different levels of care within the same location as their conditions or care needs change”. Patients move to and from hospital or ED to outpatient to clinic or primary care practice to pharmacy (s), labs, homecare agencies, and other providers. Each of these transitions is an opportunity for pertinent information to be missed or misinterpreted by patients and or healthcare providers. Lack of insurance may influence access to healthcare, including medications, and ultimately, the ability to adhere to a new discharge plan. (Development and validation of a transitions-of-care pharmacist tool to predict potentially avoidable 30-day readmissions.)

Charitable pharmacies are in a unique position to provide medications for the uninsured, allowing them to be key members of the TOC team. As with other pharmacies, they can provide medication history, including allergies and adverse reactions, and reconciliation at time of hospital admission or ED visit. Working with hospital providers (inpatient pharmacists, case managers, physicians and other prescribers), the charity pharmacist can help develop a free or affordable medication regimen for the patient, ideally prior to discharge. Check with state board of pharmacy for pharmacist scope of practice. (See Collaborative Practices and Appendices\Collaborative Practice Regulations for additional information. See example forms for referrals and delivery in

- Appendices\Transitional Care\Articles & Resources

- DOH referral form for Case Manager

- DOH Completed Referral Form for Patients See: Eligibility Guidelines Missing Information

TIP: Good Shepherd Health offers a unique service. We do a transitional care program with a local for-profit (hospital). We fill their indigent patients’ discharge meds all at once as a 90-day supply. The hospital has to approve med charges if they exceed $400. We follow up via telephone with the patient at 30, 60, 90 days. The patient gets a 90-day membership with us which means they can get their prescriptions for free or at cost. Eventually we hope to show decreased readmissions… We sell the discharge meds to the hospital at cost as well. This hospital doesn’t have an outpatient pharmacy and we bear the full cash price from the nearest (local chain pharmacy.)

Transitions of Care: Case Examples Resource, published by APhA, provides examples of pharmacy personnel roles, successes and barriers from six clinical settings.

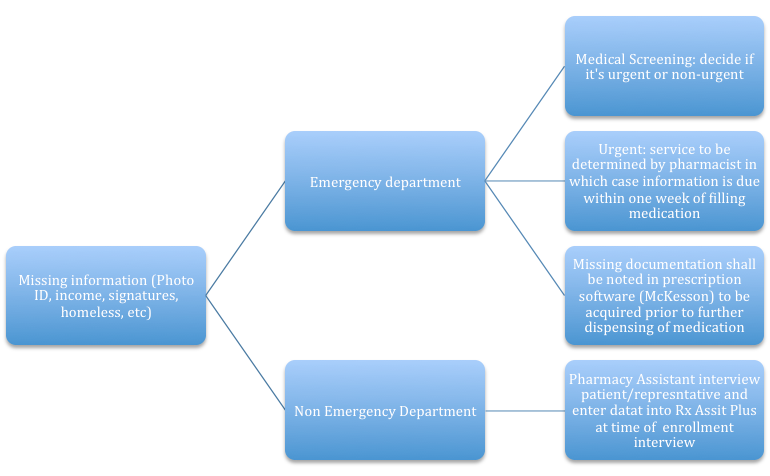

ASHP and APhA collaborated to provide a TOC best practice report, ASHP-APhA Medication Management in Care Transitions Best Practices. Each of eight best practice cases presents processes, barriers, cost justification and metrics for their various locations. Mission Hospitals discuss their safe transitions for an uninsured population. Their Mission Uninsured Safe Transitions (MUST) program includes referral at discharge from hospital and follow-up from pharmacy personnel. A sample technician phone call script is included in the article (ibid pg. 32).

See Medication Management in Care Transitions Best Practice,

University of Pittsburgh School of Pharmacy and University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) prepared a follow-up checklist for outpatient pharmacists: (ibid, pg. 43) The outpatient care transitions follow-up activities of the pharmacist include:

- Reviewing the patient’s discharge medication list and home medications.

- Identifying and resolving any medication discrepancies.

- Communicating any medication-related changes to the appropriate outpatient pharmacist.

- Identifying and resolving any ongoing medication-related problems.

- Contacting other health care professionals, where appropriate, to convey and resolve any issues identified during the post-discharge follow-up call.

- Updating the patient’s outpatient home medication list in the outpatient EHR.

- Sending a follow-up note to the patient’s primary care physician.

Transitions and Mail Order

As a mail-order charitable pharmacy, Wyoming Medication Donation Program (WMDP) uses colored notes, packaged in a zip lock bag with the prescription to alert patients. The notes notify patients of dose substitution, 90-day supply, missing information for proof of residency and/or income, eligibility renewal notice and notice that medication was not in stock. See Mail Order Charity-Only Pharmacy.

Miscommunication in the healthcare field can lead to poor health outcomes and can potentially even be life-threatening. There are a rising number of migrant patients as well as a high number of foreign-trained healthcare practitioners in the United States. This can lead to increased communication barriers between a healthcare practitioner and patient when one or both are speaking English as a second language. The lack of thorough understanding of one’s own medical condition, as well as poor understanding of the treatment and follow-up plan can lead to a number of problems. These problems may include but are not limited to poor adherence to treatment plans consisting of medications and/or diet and lifestyle recommendations, which can lead to uncontrolled health conditions, poor health outcomes, and increased morbidity and mortality. Patients with low health literacy are often associated with poor health outcomes, increased hospitalizations, and an overall decreased quality of life1.Taking the time to ensure a patient’s proper understanding of points discussed with the healthcare team can result in better outcomes and decreased costs to the individual patient, clinic, and health system. Patients with language barriers are also less likely to have a consistent provider of medical care leading to a poor continuity of care further contributing to the array of health problems a patient may face. Language barriers can deter patients to ask questions about their treatment and prevent them from taking an active role in managing their overall health. It is important to overcome these language and communication barriers so we can have a positive effect on patients and support them in becoming champions of their own health.

The resources provided below can be used to overcome these language barriers:

| Resource | Description | Languages Available for Patient Materials | Cost |

| RxTran | RxTran offers pharmacies the service of providing prescription drug labels, auxiliary labels, and patient medication guides in different languages. Currently they offer SIG translation into 17 different languages. The also offer over the phone interpreting in over 150 languages available 24/7.

*Figure 1-2 |

English, Arabic, Bengali, Chinese (traditional & simplified), French, German, Greek, Haitian Creole, Hindi, Korean, Italian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Vietnamese | $80-100/ month depending on number of locations, pharmacy software, and languages needed |

| Meducation | Meducation is a cloud-based solution, accessible to healthcare providers within their clinical workflow via their EMR system or as a standalone solution, which delivers medication instructions.

http://www.fdbhealth.com/meducation-overview/

*Figure 3-7 |

Over 20 languages | Contract specific pricing |

| VUCA Health | VUCA Health is an organization that gives patients the ability to quickly and conveniently access thousands of medication-specific videos in the MedsOnCue library by clicking on a link in an email or text message, or by scanning a QR code printed on prescription labels and patient information sheets.

*Figure 8 |

Videos available in English and Spanish | Contract specific pricing |

| Lexicomp | Lexicomp is a drug information resources that also gives you access to patient medication hand outs

http://www.wolterskluwercdi.com/lexicomp-online/ *Figure 9 |

English, Arabic, Chinese (traditional & simplified), French, German, Greek, Creole, Japanese, Korean, Italian, Polish, Punjabi, Portuguese, Russian, Spanish, Tagalog, Turkish Vietnamese | -$285/year for mobile app

-$795 for mobile app and online |

| Micromedex | Micromedex is a drug information resources that also gives you access to patient medication hand outs https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/home/dispatch |

English, Spanish | Contract specific pricing |

| Access Pharmacy | AccessPharmacy is an online pharmacy resource designed to meet the demands of pharmacy education and practice today. AccessPharmacy gives instant access to videos, games, Q&A, leading pharmacy textbooks, information about drugs, herbs and supplements, as well as patient drug handouts. | English, Spanish | >$595/year |

| Clinical Key | Clinical Key is a clinical search engine that gives access to drug monographs, guidelines, journals, books, and patient education handouts. | English, Spanish | $499/year for internal medicine package |

| Medline Plus | MedlinePlus is the National Institutes of Health’s website for patients and their families and friends. It provides information about diseases, conditions, drugs, supplements and wellness issues in patient friendly information. | English, Spanish | Free |

| HealthReach | HealthReach offers easy access to FREE quality multilingual, multicultural public health information including documents, audio, and videos for those working with or providing care to individuals with limited English proficiency. | English, Albanian, Amharic, Arabic, Armenian, Bengali, Bosnian, Burmese, Cape Verdean Creole, Chinese (traditional and simplified), Chuukese, Dari, Dzongkha, Farsi, French, German, Gujarati, Haitian Creole, Hakha Chin, Hindi, Hmong, Ilocano, Indonesian, Italian, Japanese, Karen, Karenni, Khmer, Kinyarwanda, Kirundi, Korean, Kurdish, Lao, Levantine, Malay, Marshallese, Nepali, Oromo, Pashto, Pohnpeian, Polish, Portuguese, Punjabi, Russian, Samoan, Serbo-Croatian, Somali, Spanish, Sudanese, Swahili, Tagalog, Thai, Tibetan, Tigrinya, Tongan, Turkish, Ukrainian, Urdu, Vietnamese | Free |

Recognizing language barriers in healthcare as a significant issue, some states have also started to require pharmacies to provide labeling in multiple languages to patients. The following table lists states that have requirements for multi-language labels:

| State | Requirement |

| California* | All pharmacies or facilities which dispense medication are required to provide translation of the 15 SIG codes on the Board of Pharmacy of California website. The board has interpretations of these in 5 languages which include Spanish, Chinese, Korean, Russian, and Vietnamese. |

| New York* | Chain pharmacies are required to provide free competent oral interpretation and written translation services of prescription drug labels, auxiliary warning labels, and other written materials to limited English proficiency patients. The primary languages required are Chinese, Spanish, Russian, and Italian. |

| Texas* | Whenever possible the directions of use on a prescription container label should be provided in the patient’s preferred language. Drug name shall be in English. Translations of prescription medication labels should be produced using high-quality translation process. |

| North Carolina | The NC Board of Pharmacy provides signs for pharmacies to put up for Spanish speaking patients informing patients they can obtain their prescription medication instructions in Spanish. |

*These states legally require pharmacy label translation.

Below are some examples of patient labels and handouts from these services

Authors:

Onkur Lal, Pharm.D. Candidate 2018 Virginia Commonwealth School of Pharmacy

Zeshan Mahmood, PharmD, Clinical Pharmacist

NOVA ScriptsCentral

As with translations, miscommunications through an interpreter can lead to poor health outcomes. Interpretation is a skill requiring practice both by the interpreter and the healthcare professional. See Appendices\Transitional Care\Articles & Resources\How to use an Interpreter.docx Family members and friends may not be accurate in interpreting. There also may be information exchanged that would violate patient privacy with a family member or friend. Interpretation could be altered to “protect” the patient or reflect the interpreter’s perspective rather than the patient’s. Do not use a minor for interpretation. Ideally, a qualified interpreter is used for the most accurate interpretations. When the community charitable pharmacy is likely to serve multilingual patients, hiring multilingual staff and training them as an interpreter is a cost-effective, privacy-compliant option.

Whether using technology (tablet or phone based) or a live qualified interpreter, communication needs to be clear and personal.

- Maintain eye contact with patient, not interpreter. This will give nonverbal clues to patient understanding.

- Use language that is easily interpreted and non-technical when possible.

- Speak directly to the patient, not “Tell her…”

- Be patient. What in English is a short sentence may be multiple sentences in another language. The interpreter may need to think what the best way to interpret what was said by patient or healthcare provider.

Use of technology for interpretation takes practice. See Interpretation for resources. Before ending the session, verify the patient clearly understands and has had questions answered and the pharmacy has all the information needed.

Recognizing language barriers in healthcare as a significant issue, some states have also started to require pharmacies to provide labeling in multiple languages to patients. The following table lists states that have requirements for multi-language labels:

Illiteracy, especially in English, may be a factor in adherence contributing to readmissions. Offering labels, (See Pharmacy Translations) counseling and education in patient’s first language is a best practice in service, appreciated by patients and healthcare referral sources. Picture handouts for use of devices and pictograms for medication directions may provide clarity. They can be posted at home as a reminder for compliance and/or shared with caregivers. They can be photographed to keep on a patient’s phone. (Example handouts are in Appendices\Transitional Care\Pictograms)

Example: pictogram for H. pylori Treatment (HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport, 2019)

| Medication | Manana | Noche | |

| Clarithromycin

500 mg |

1 | 1 | Por 14 dias

For 14 days |

| Amoxicillin

500 mg |

2 | 2 | Por 14 dias

For 14 days |

| Omeprazole

20 mg |

1 | 1 | Por 14 dias

For 14 days |

| Yogurt | 1 | 1 | Por 14 dias

For 14 days |

Besides medication reconciliation and dispensing, other services can be offered to complement those available at referral sources.

- Delivery to patient prior to discharge

- Follow-up phone call to patient

- Targeted MTM

- Therapeutic Outcomes monitoring (A1c, blood pressure, lipids, etc.)

- Medication and disease management through a collaborative practice agreement

- Device training

- Motivational training

- Smoking cessation

- Immunization evaluation (and administration if available)

Referring patients to their primary care provider for regular appointments may help to maintain compliance and assess health status. Issues of adherence (too much or too little), behavioral health, ineffectiveness of treatment or device utilization are all opportunities to alert and work with providers and, ideally, keep patients out of the hospital.

Charitable pharmacies often recognize patient needs for community services that may not be being met. Example: a diabetic patient without access to a stable food source. United Way 211 may offer a list of local community services including:

- Food banks and pantries

- Clothing

- Diapers

- Shelter/housing

- Transportation

NOVA Scripts Compass offers a search for free and reduced cost services like medical care, food, housing and more in your immediate area by zip code.

Establishing reciprocal referral relationships with other community providers is a win-win for patients and lists #4 on the Top 10 Ways to Grow Your Charitable pharmacy.

“For people discharged from prison, managing chronic illness is often a lower priority than finding housing, employment, and food.” Transitions Clinic Network: Challenges and Lessons In Primary Care For People Released From Prison. In this study, approximately 40% of those released from incarceration reported being uninsured, though some were eligible. A referral relationship with correctional agencies (prisons and parole and probation officers), as well as recovery and other community service providers offers an opportunity to connect this population to medication access and a charitable pharmacy. See Fund Development Decision Tree.

Get access to the full playbook

Get instant access to the full playbook, with more than 150 pages of valuable guidance, case studies and resources to help you develop your charitable pharmacy.