Inventory Management is one of the keys to a successful charitable pharmacy. Devolving and maintaining inventory processes will allow the pharmacy to maximize the use of limited resources and to serve patients to the best of their ability.

This chapter will cover concepts that may be considered when developing and managing an inventory including: developing a formulary, sourcing medications which may include donated medications, prescription assistance programs, developing standing orders for therapeutic substitution, proper drug disposal, computer systems, and routine inventory management tactics.

As defined by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), a drug formulary is a continually updated list of medications and related information, which represents the clinical judgment of physicians, pharmacists, and other experts for the treatment of disease and promotion of health. In a community setting, a formulary addresses the therapeutic, economic, educational, and rational evidenced-based drug use of the population being served.

In a community pharmacy, a formulary is a list of medications available at the pharmacy to meet patients’ needs. It can be shared with prescribers explaining medications that are available at the pharmacy and to reduce or restrict the inventory of the pharmacy.

The formulary will likely be comprised of the most commonly used medications to treat chronic conditions such as hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, asthma, mental health, and others affecting patients across the United States. Medication can be selected from each therapeutic class to help manage chronic conditions based on clinical evidence from nationally supported disease state treatment guidelines and medication monographs (adverse reactions and interactions). See Dispensary of Hope Formulary Development and Utilization. Factors that affect the formulary include availability of medication along with class changes (new drugs that become available, brand to generic switch, and generic to OTC changes), medication shortages, patient allergies and/or adverse events, prescribing changes, guideline changes, adverse effects and alerts, and pharmacoeconomic shifts.

Considerations

Start small and with a lean inventory, knowing that pharmacy volume can take a while to build up at first. This reduces waste, staff time, and inventory space.

Set up an inventory by identifying drugs currently dispensed to the uninsured patient population, and target these drugs first when ordering. Ordering one of each medication is not recommended as it would require additional shelf space (which may be limited), and these additional drugs may go unused and destroyed.

Share your formulary with prescribers regularly (monthly, quarterly) so they may generate prescribing habits to use what is available through your “free” vendor inventory.

Site example: Embed the formulary in the EMR, if possible, or print copies of the most recent formulary to share in discharging patient medical records.

If getting requests for drugs not available, communicate and educate the prescribers:

- Share the formulary with them and ask which medications they will likely be needing, then order those.

- Ask the prescribers if there are any medications they may need that are not on the formulary. Look for ways to source these if possible.

- Keep track of what is available at your pharmacy. Share this available inventory list on a regular basis so prescribers know what is on hand and can be filled.

- Utilize therapeutic interchange to recommend alternative medications to prescribers. For instance, the prescriber asks for fexofenadine and only cetirizine is available at your pharmacy. Recommend a change to cetirizine to prevent the patient going without medication.

- Consider developing a collaborative practice agreement (CPA) with practitioners, allowing the pharmacist to automatically dispense medication from an approved protocol. Therapeutic interchange, with approved parameters, fits well within a CPA. Several states already have collaborative practice agreements in place.

TIP: Some pharmacy software resources offer deep discounts for charitable pharmacies. Be sure to ask.

Many software programs are available that receive prescriptions and aid in dispensing medications for use in community pharmacies. These programs help manage inventory, workflow, accounts, and assist in record keeping. Beyond those necessary for running a pharmacy, there are features that are especially suited for a community charitable pharmacy. Most systems are adaptable but may require creativity on the part of the pharmacist and the software provider to develop. Features that may be available or adapted involve labeling, patient records, counselling, reporting, and billing. See Dispensary of Hope Pharmacy Software Webinar.

Patient Enrollment Criteria and Documentation Data

Patient eligibility for charity services frequently varies from that normally used when filling a routine prescription. See Eligibility Guidelines. This may require creating customized fields. Additional information needed beyond demographics and allergies/sensitivities include:

Income/Federal Poverty Level (FPL)

- Size of household: adults/children

- Preferred language

- Ethnicity (if required)

- United States residency status

- Insurance status (uninsured, pending, ineligible)

- Eligibility for other assistance programs

- Referral source

- Veteran

Additional software may screen patients for insurance.

Maintain patient database by removing patients who have not filled a prescription within a set period of time as determined by the site.

Systems are upgrading to accommodate documentation of patient interactions and health information. Exchange of health information allows pharmacists to improve their clinical services—especially medication therapy management (MTM). Hospitals and clinics may allow a view-only link to access patient data. Access to lab values and other trackable measures (blood pressure, weight, etc.) may allow opportunities for collaborative practice agreements. Documentation of clinical interventions within the patient profile allows for metrics collection and tracking outcomes even when this is not a billable service. By 2018, pharmacy systems should be Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) compliant, allowing trackability of outcomes pertaining to reimbursement by Medicaid and Medicare.

Bidirectional systems allow other healthcare providers access to pharmacy information and vice versa. Some systems accommodate linking multiple systems for information exchange. Following control substance prescriptions is an example of many healthcare providers, including prescribers and pharmacists, having access to pertinent patient data across a geographical area. Connecting systems may allow pharmacist documentation of a medication problem or recommendation to be transmitted directly to the prescriber. See Health information technology in the community pharmacy.

Label and Patient Information Capability

Specialty labeling for the prescription, bag, signature log and patient information may be useful and necessary in a community charitable pharmacy.

- Features for multiple languages. The ideal patient label system uses numerals rather than alpha characters (2 instead of two) as these are usually more legible across languages. Written patient education information also available in multiple languages. See Pharmacy Translations.

- Pictogramsfor patients who do not read and to enhance understanding across languages. See Illiteracy, Pharmacy Translations, and Appendices\Transitional Care\Pictograms.

- Pricing of “0” for medication dispensed at no charge to patient.

- Alerts for information needed prior to dispensing including renewal of eligibility, missing documentation, and special patient counseling.

Tracking Product from Multiple Vendors

In compliance with the Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA), pharmacy management systems help track product to the patient level. See Tracking.

Options include:

- Establish a separate billing code (even though not billing) for each vendor for compiling reports.

- Set patient cost based on specific billing codes: “0” for no copay or a set price for safety net

- Adapt NDC codes for products provided by more than one vendor (check with system provider on best way to do this).

- Change product description to differentiate vendor

- Program system to pull product from nonprofit vendor first

- Creating a “dummy” NDC eliminates Drug Utilization Review (DUR) function, removing safety features of system.

- Use Wholesale Acquisition Cost(WAC) cost rather than Average Wholesale Price (AWP) when determining value of product from a non-profit vendor. The WAC price is based on what a pharmacy would pay for a product if purchased from a pharmacy wholesaler.

- Manually add inventory received from a nonprofit vendor to allow reporting when automatic ordering is utilized

- Drug recall report are based on vendor billing code and specific NDC.

- When in a mixed-model pharmacy serving both charitable and billable patients, having “virtual” facilities helps create a less manual process and makes tracking nonprofit vendors easier.

Reports and Metrics

In addition to inventory, pharmacy management and state-required reports, vendors may require specialty reporting. These reports may need to be built specifically for the data being captured. System providers and other charitable pharmacies using similar systems are two resources to check when developing a new report. Reports exported as excel spreadsheets can be adapted using excel formulas.

Example

Total number of 30-day prescriptions:

Create an excel report that looks at the day supply.

=IF(L6<31,1,IF(L6<61,2,IF(L6<91,3,IF(L6<121,4,IF(L6<151,5,(IF(6<181,6))))))

Number of Unique Patients:

Create an excel report that looks at patient name.

=IF(C6=C7,0,1)

Number of Patient Encounters:

Create an excel report that looks at the patient name and the date the prescription was filled.

=IF(C7=C6,IF(B7=B6,0,1),1)

Dispensary of Hope Link to Webinars Best Practices in Technology and Pharmacy Software Webinar.

Adapting fields within a pharmacy system is an option to create a specific report or a report with additional information. This can be done by adding the following:

- A prescriber state license number to a pull-able, non-used prescriber field to be used in a report that requires state license but not DEA number.

- A pull-able blank patient field populated with the patient Federal Poverty Level (FPL).

Clinical Reporting

RxAssistPlus is a clinic-friendly system adaptable for collecting and reporting many types of clinical data. Patient enrollment criteria can be collected and is useful for demographic reporting, including language, referral source, income compared to FPL, and more.Systems such as Outcomes MTM and Mirixa are platforms for collecting and measuring the impact of clinical data and interventions. They allow disease-specific medication management, track adherence, or if additional medication is needed for patient.

These systems can track the clinical impact of services on patients served. Outcomes can be measured in severity, type, and number of interventions performed. As well as the total estimated cost avoidance to other healthcare systems (hospitalizations, ED visits, etc.) and total service worth if the services were billable to insurance.

See the chapter on Measurements, Evaluation and Outcomes and Appendices\Metrics for more reports and how they can be used. Implementation of performance metrics to assess pharmacists’ activities in ambulatory care clinics presents measurable pharmacist functions that impact patient outcomes and mechanisms used to document these services.

TIP: Good Shepherd Health uses Prosperworks to keep patients informed and expand the practice.

Customer Relationship Management (CRM)

Patient engagement and keeping patients informed is important to the growth of a charitable pharmacy. CRM covers a broad set of applications for business management, workflow, productivity, marketing, and more. These software systems help manage relationships and expectations with patients, funders, stakeholders, colleagues and others who have a relationship with your charitable pharmacy. Patient interactions and other contacts are documented giving team members access to current information and managers the ability to track productivity. Patientriciti is specifically for healthcare providers, allowing personalized engagement with patients based on demographics and clinical/behavioral data to improve outcomes. See Marketing for resources.

Volunteers and Scheduling

See Human Resources/Volunteers and Volunteers for resources.

Medication Storage

Some meds may require segregated storage (and destruction). Vendors may require segregation of the products they supply. Many will also require separation of the virtual inventory in the pharmacy software system. Be sure to check with your software vendor on this capability. Oncology and other hazardous medications may be segregated as well (warfarin, estrogen and progestin products, finasteride, lindane, nicotine, nitroglycerin). See CDC Antineoplastics and Healthcare Environmental Resource Center for current listings.

Many medications are temperature sensitive. Document refrigerator temperatures twice daily or as required by state regulations. Medications stored at room temperature may also be affected by extreme temperatures (inhalers, nitroglycerin, capsules, etc.). Develop a plan should extreme temperatures occur (loss of air conditioning or heat). See example of temperature log.

Beyond Use Dates

Medications are labeled with a beyond use date (expiration date); beyond which they should not be used or dispensed for use. These dates are subject to change depending on storage conditions and repackaging. Products should be reviewed regularly for outdates. The following are suggested procedures:

- When a new product is shelved, ensure the product soonest to outdate is in front (rotate stock).

- Regularly, usually quarterly, all products should be reviewed, and outdated product removed to a quarantined area for destruction.

- Product whose beyond use date has been changed due to storage considerations should be stored separately from regular stock and clearly labeled to prevent confusion.

- When repackaging medications, use the actual beyond use date up to 1 year from repackaging.

Cycle Counts

Instead of counting the entire inventory once a year, WMDP does “Cycle Counts”. Fast movers are counted quarterly and the whole inventory over the course of the year. The top fast movers are divided up over a 12-week cycle. Usually about 10 drugs are counted per week. For the full inventory, one to two letters of the alphabet are assigned per month. For instance, all “A & Z drugs” are counted in January. If an inventory count is significantly off, counts are checked and adjusted more frequently. Inventory counts on all drugs that show a negative inventory are verified at the end of each month. With the bubble packs and so many NDC’s in stock, a full year inventory was not manageable, but this process made it manageable. The inventory is posted online to assist with patient referrals. Cycle Counts keeps the inventory more accurate.

Overstock Medication

For charitable pharmacies accepting direct donations, there may be an abundance of donated medications that have a low demand. This can increase workload significantly when adding into inventory, maintain storage, include in cycle counts, and then subtract when reach beyond use date. To improve efficiency, a list is kept of medications that are currently in overstock. When donations are sorted, items on the overstock list are automatically disposed. The list is updated every 2 weeks. This process has proven to improve program efficiency.

Medication Recalls

When using directly donated medications, there may not be a routine recall notice received at the pharmacy. FDA provides a weekly report regarding recalled medications. To use the report:

- Narrow the report to drugs only

- Check report for NDC’s that are on file at the pharmacy

- Check inventory for recalled Lot/Expiration numbers

Pharmacies who provide donated medication to dispensing sites must notify those sites regarding any recalls that affect medication received from the source pharmacy.

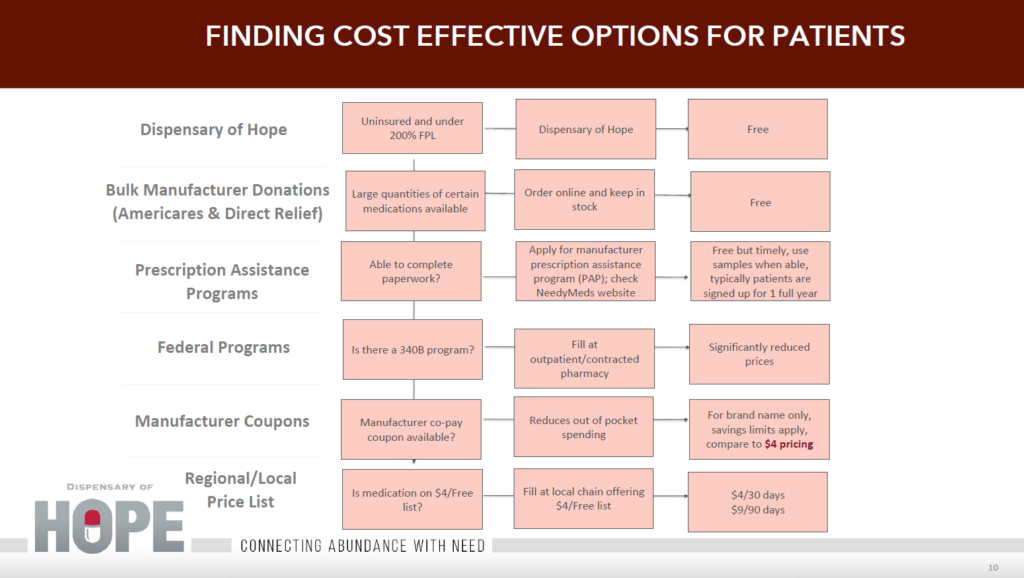

As a community charitable pharmacy, a primary goal is to provide medication to uninsured and underinsured patients for free or as economically as possible. Various sources exist to supply medications for this population.

Fig. 1

Vendors

Many vendors exist for “free” medication. Some charge an annual fee for membership which includes ordering available medications and shipping to your facility. Some vendors allow enrollment without a fee, allowing pharmacy to order from available products. Products may include medical devices (e.g. glucometers, test strips, etc.) as well as over-the-counter meds (OTC), but products and medications are not always available. (Direct Relief, Americares, Dispensary of Hope, SIRUM, etc.) Seek legal advice when entering into a contract to ensure meeting all state and local regulations.

Possible medication resources:

- Americares

- Direct Relief

- Dispensary of Hope

- NeedyMeds

- Partnership for Prescription Assistance

- RxOutreach

- SIRUM

- Xubex

Some pharmacy wholesalers and distributors are listed in Vendors. Pharmacy management software may be available through a wholesaler as well. Contracting with another pharmacy may be possible if within state and local regulations and follow DSCSA. See Tracking the Medication Supply Chain.

Not all vendors offer next day delivery. Many are weekly or monthly. Plan ahead!

Each medication source may have its own procedures for storage, record keeping and handling of expired meds. Ensure careful attention and documentation as per vendor’s policies.

340B

The 340B Drug Discount Program is a US federal government program created in 1992 that requires drug manufacturers to provide outpatient drugs to eligible health care organizations and covered entities at significantly reduced prices. Covered entities that participate in the 340B program may contract with pharmacies to dispense drugs purchased through the program on their behalf. Two useful resources regarding 340B as used in an outpatient pharmacy are:

The Bridge to 340B Comprehensive Pharmacy Solutions in Underserved Populations. This resource is from 2004 and there have been significant regulation changes since that time but provides information regarding the intent of the 340B program and applications to pharmacy.

Understanding 340B and Contract Pharmacy. This resource is from McKesson wholesaler, 2015, and presents a business approach to utilizing 340B with a contract entity.

Considerations:

- If a charitable pharmacy works with a covered entity registered under the 340Bprogram, then they should be set up as a contract pharmacy. Inventory is virtually tracked through a split billing system and replenished with 340B drugs based on appropriate accumulations in eligible patients of the covered entity or child sites.

- Free or donated drugs must be kept as separate inventory(and are not part of the 340B program).

- The Virtual Inventory is mixed between purchased medications and 340B replenished medications but can NEVER be mixed with free or donated drugs.

- If the charitable pharmacy is part of the 340Bcovered entity, then segregated 340B inventory could be maintained (if the covered entity chooses not set the charitable pharmacy up as a contract pharmacy) but must follow the rules of the covered entity type to prevent duplicate discounts, adhere to the Group Purchase Organization (GPO) prohibition (if applicable) or adhere to the orphan drug exclusion (if applicable) and can only be used in an eligible patient based on the 340B statute.

- Proper auditing MUST occur to make sure 340Bdrugs and free or donated drugs are completely separate and are not part of the 340B records.

Vouchers

Vouchers can be manufacturer coupons, where medication dispensed is reimbursed by the manufacturer, or from a healthcare facility that contracts with the pharmacy for reimbursement, usually at a discounted rate. Medication dispensed using a voucher cannot be taken from free or donated stock.

Another type of voucher used to supplement gaps in stock is between pharmacies. A contract is established with a retail pharmacy that is able to fill prescriptions for approved patients at an agreed upon rate. The voucher is provided by the charitable pharmacy to the patient or faxed to the contracted retail pharmacy. The patient picks up the prescription from the retail pharmacy. The retail pharmacy submits a report monthly or as contracted for prescriptions filled. Reimbursement occurs once the invoice/report is verified. Grant funds may provide for the cost of these vouchered prescriptions.

Manufacturer Bulk Replacement

Some manufacturers offer a bulk replacement program allowing the pharmacy to stock the medication and act as the PAP program manager. Manufacturer programs require their own eligibility requirements, policies, monthly and annual metrics, auditing and volume of med dispensed. See Manufacturer Bulk Patient Assistance Programs

Direct Donations

Legal regulations regarding donated sample medications can be found in Appendices\Regulatory\Sample State Regulations.

Upon receipt, donations should be inspected by pharmacist or qualified pharmacy technician. Inspection includes:

- Donation record accurately describes drug samples

- Beyond Use Date (expiration) is within limits

- Sample labeling is not mutilated, obscured, or detached from packaging (primarily donations previously dispensed as in reclamation.)

- Sample does not show evidence of storage or shipping condition that might have affected it stability, integrity, or effectiveness.

- Sample still on the market and not subject to recall

- Sample shows no evidence of contamination, deterioration, or adulteration

- If the sample does not pass the inspection, it is destroyed or returned to the donor and documented on the donation record.

Donations from Prescribers and Practices

Branded samples including insulin and inhalers may be available from providers and practices that are willing to donate directly to your charitable pharmacy. NovoMedLink has an online service to order sample insulin. Hospitalists at local hospitals may be willing to donate sample insulin to provide for their uninsured patients at discharge. Clinics may be willing to donate excess sample medication or may have eliminated medication cabinets and be willing to acquire donations for a charitable pharmacy. Internists and other providers who prescribe insulin in their practice may be willing to order and donate samples. Pulmonologists may have access to excess inhalers; cardiologists to antithrombolitics and heart failure meds. See Insulin and Inhalers for a presentation regarding possible sources. Track and Trace compliance is mandatory.

Sample Medications

TIP: Find Physician Practice Champions willing to donate samples monthly. Celebrate them at an annual Medical Association meeting and in newsletters.

Samples come with their own set of regulations. To stay compliant, check with individual state. In general:

- Samples require DSCSA Track and Trace compliance when donated from a healthcare practice or facility.

- Samples are dispensed in the original container. Do not open containers to dispense a partial quantity in an original container or combine samplesinto a separate vial.

- Each sample container requires an individual patient label.

- Boxes of blister pack samples may have one label attached to several boxes.

- Quantities dispensed are in multiples of sample original container, not usually 30, 60, 90.

- Samples beyond the use date are not returned to manufacturer or vendor for credit or destruction. Record of destruction (See Track and Trace) still needs to be maintained per policy and/or state regulations.

- Oncology and hazardous waste samplesand meds have specific destruction Follow the direction of disposal vendor.

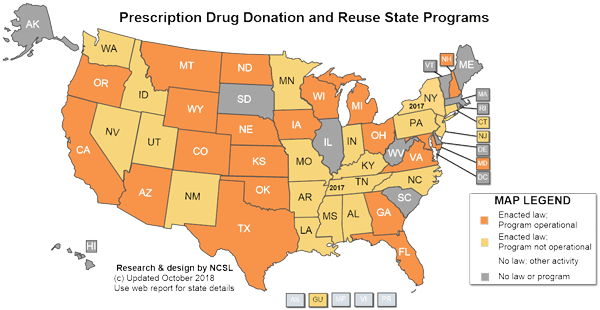

Across the country and beyond, drug donation programs are quietly emerging as a practical channel to connect patients in need of assistance with unused prescription medications. The World Health Organization has developed international guidelines for humanitarian relief as a basis for national and institutional guidelines. The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) reports that 42 states have legislatively created drug donation programs, of which 20 states have operational programs.

Tip: At WMDP, we have enough medication donations to fill about 2/3 of our prescriptions. The other 1/3 is filled using product ordered from a nonprofit vendor or purchased using grant funds.

Direct donations from patients and institutions (skilled nursing facilities, prisons, etc.) vary by state. Check with state pharmacy regulations to determine if donations are allowed and any restrictions that exist. (See Figure 2) and Appendices\Regulatory\Board of Pharmacy state regulations 1.2017.xlsx)

State Rx Reuse Snapshot

State Prescription Drug Return, Reuse and Recycling Laws

10/1/2018

Pharmaceutical donation and reuse programs are distinct prescription drug programs providing for unused prescription drugs to be donated and re-dispensed to patients. Such drug repository programs began with state legislative action in 1997. As of fall 2018 there are 38 states and Guam with enacted laws for donation and reuse.

STATE REUSE PROGRAMS: Four Spotlight Examples (as of mid-2018)

- Iowacreated its program in 2007 and has served 71,000 patients and redistributed $17.7 million in free medication and supplies donated to people in need (taken from 2016 Performance Update).

- Wyoming’s Medication Donation Programwas created in 2005 and has helped Wyoming residents fill over 150,000 prescriptions, adding up to over $12.5 million.

- Oklahomacreated its program in November of 2004 and has filled 227,603 prescriptions, worth about $22,518,462 based on the average wholesale price of medication, through the end of May 2018.

- Georgia’s return and reuse repository, despite being a newer program, has quickly grown into one of the nation’s more successful programs.

See: Medicine donation program helps many Georgians who can’t afford what they need– GA news article, Aug. 7, 2018

Pharmaceutical donation and reuse programs are distinct prescription drug programs providing for unused prescription drugs to be donated and re-dispensed to patients. Such drug repository programs began with state legislative action in 1997.

Although many states have passed laws establishing these programs, almost half of these states do not have functioning or operational programs. “Operational programs” are those states that have participating pharmacies, charitable clinics, and/or hospitals collecting and redistributing donated drugs to eligible patients. Some common obstacles are the lack of awareness about the programs, no central agency or entity designated to operate and fund the program, and added work and responsibility for repository sites that accept the donations.

Nationwide Rx Reuse Snapshot

- As of mid-2018, 38 states and Guam had passed laws establishing drug redistribution programs. Many of these programs are not operational or small, but successful programs are growing. A few measures have been repealed.

- Twenty-one states currently have enacted laws with operational repository programs.

- At least a dozen and a half additional states are categorized as having non-operational enacted laws. New York’s Nov. 2016 law is the latest.

- Filed legislation: In 2015-2016 there were 19 bills regarding this topic introduced throughout the states and the District of Columbia.

Cancer-Specific Programs: The enacted laws in 13 states—Colorado, Florida, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Utah, Washington, and Wisconsin—allows them to accept and distribute cancer-related prescription drugs.

NOTE ON SAFE DISPOSAL:

This NCSL report does not include the numerous programs that coordinate disposal and safe destruction of unwanted drugs, either legal or illegal. Such disposal programs are designed to prevent re-use, rather than aid the health of needy patients. Disposal policies and laws are handled by the NCSL Environmental Health Program (link).

Comparison of Provisions in Enacted Legislation

- Most state programs have a number of provisions in common:

- No “controlled substances” medication is allowed to be accepted or transferred.

- No adulterated or misbranded medication is allowed to be accepted or transferred.

- All pharmaceuticals must be checked by a pharmacist prior to being dispensed.

- All pharmaceuticals must not be expired at the time of receipt.

- All pharmaceuticals must be unopened and in sealed, tamper-evident packaging.

- Liability protection for both donors and recipients usually is assured.

- Some current differences in legislation across states include:

- Drugs accepted for re-distribution: Prescription only vs. Over the Counter vs. Drug specific (i.e. only cancer drugs)

- Eligible donors, recipients and patients.

- Minimum number of months before expiration date.

- Protocol for transfers and repackaging.

- Maximum dispensing fees

- Centralized / decentralized

- Programs funded or unfunded

Sources of Repository Medication

Drug donation regulations are governed at the state level and contrast greatly from state to state. Most state programs have substantial restrictions on who can donate and what types of prescription products or supplies may be donated. Very strict safety rules also apply, intended to protect the patient that ultimately obtains and takes the medication.

Contributed medications that do not meet the donation criteria must be incinerated or destroyed. Because of the donation criteria, any medications dispensed in an amber vial or dispensed in a manner that does not use sealed, tamper-evident packaging is strictly prohibited. As a result, many operational programs rely on long-term care dispensing pharmacies as the primary source for donated medications. The 31-day or less blister packs that are used in long-term care settings allow for easy visual inspection for drug identification and tampering. Dispensing pharmacies for long-term care have welcomed drug donation repository programs as an economical option to dispose of previously dispensed but unused medications.

Example:

Wyoming state law allows Wyoming Medication Donation Program (WMDP) to collect donations from any source having sealed, in-date medication (within 5 months of beyond us/expiration date.) Donations can be from the public or a facility that has unused medications, including nursing homes, detention centers, prisons, hospice, samples from offices, and other facilities with patients in their care that have bubble pack meds.

Excluded medications include: refrigerated, controlled substances, broken or half tablets, packets with multiple pills in the bubble, beyond use or expired, short-date (5-month expiration from the date of donation or beyond use date), and medical supplies.

All donated medications should be inspected as described above. See Direct Donations

Patients Served

Drug donation programs are designed to aid uninsured and underinsured patients with limited incomes. These programs are not intended to provide medication assistance in lieu of state or federal programs, but do serve patients who need short-term assistance, such as an insured, low-income patient who cannot afford a prescription co-pay, an individual who has lost employer-provided insurance, or a senior who has reached the Medicare coverage gap. In many cases, a drug donation program provides critical medication access in instances where the patient would otherwise go without.

Although some states allow the drug donation program to dispense directly to the patient in need, many programs are licensed in their state as a wholesale distributor. As distributors, the drug donation programs supply community pharmacies or medical facilities such as a free medical clinic or federally qualified health centers with donated medications that will be dispensed to patients in need. Once the donated medications are received by the pharmacy or medical facility, the medications are dispensed to the patient in its donated form; however, some states also allow the dispensing medical facility to repackage the donated items in a format that is consistent with retail pharmacies.

National Conference of State Legislatures Staff. State Prescription Drug Return, Reuse and Recycling Laws. National Conference of State Legislatures. (2017, March 31). Rosmann J. Drug Donation Repositories: State Programs to Leverage Scarce Health Resources. Inside Pharmacy. 2013;1:13-14.

Reclamation Resources

The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) is the best resource to see what is happening across the country regarding medication reclamation, however the information is a little outdated since it largely relies on states self-reporting new updates and changes. See NCSL for updates. New York and other states may be added to the list with enacted laws.

A recent story in ProPublica, December 1, 2017, highlights the work of several states to make programs operational. See More States Hatch Plans to Recycle Drugs Being Wasted in Nursing Homes.

Consider medication destruction as part of a reclamation program or any program largely based on donations. Of all the medication donated to WMDP, about 25 per cent ends up in disposal, based on pounds of disposal versus pounds of donation collected. This can influence space, staffing and volunteering, and provide opportunities for partnering with the community. See Medication Destruction

Create a Unique Safety Net List

Creating your own formulary and finding affordable sources for those medications is necessary to support low income patients. For example, provide a “safety net list” of medications available for a small fee ($1, $3) or no charge to provide patients in need when medications are not available for free.

Tip: What therapeutic gaps exist in the formulary you want to provide? (Antibiotics, ophthalmics, dermatologics, inhalers, cardiac, neurologic or psychotropic meds, insulins, diabetic supplies, spacers for inhalers, others?) What have other charitable pharmacies done to fill these gaps? What options can you utilize?

For example, Saint Thomas Health hospital in Nashville, TN, offers these goals for inventory for a Safety Net Program:

- Offer at least one or two medications in most therapeutic drug classes since some brand & generic meds are not always available through “free med” vendors

- Provide a drug formulary that would be more stable and affordable than other community programs (including $4 lists)

- Fill in any therapeutic gaps not provided by “free med” vendors, $4 lists, etc.

- Provide a one-stop shop (since transportation can be an issue)

- Guidelines for fee schedule

Low-Cost Mail Order

Vendors such as RxOutReach, Xubex, GoodPill, and HoneyBee Health offer eligible patients discounted pricing on their formulary medications. Prescriptions are mailed and usually for a 90 day supply. A credit or debit card or check may be required for payment.

Utilization of manufacturer Patient Assistance Programs (PAPs) may be able to supply the long term needs of eligible patients for medications not available or in short supply at your pharmacy (e.g. inhalers, insulin).

Options for Insulin

The Dispensary of Hope team frequently hears from safety net providers across the country about the need for access to insulin. Caregivers for vulnerable populations often struggle to meet all the medication needs for their diabetic patients. Due to the high cost of insulin therapy, many patients still struggle to control their blood sugar levels and either skip doses or do without which ultimately leads to poor health outcomes. 1 Offering the most vulnerable patients, those who could not afford even a $25 vial, access to donated insulin can impact their health and reduce their risk of heart attack, blindness, and amputations. Providing donated insulin See Direct Donations for those patients most in need can save communities and health systems billions of dollars in uncompensated medical care.1,2 Diabetes can be controlled if managed properly. Providing medication for those most in need can help those patients lead healthier lives and can change a diabetes diagnosis from a terminal one to a manageable disease.

The “CINCI” study was published in 2017 by St. Vincent de Paul Charitable Pharmacy of Cincinnati after they followed patients switched from basal/bolus to twice daily dosed OTC insulin. This choice to switch to twice daily insulin reduced costs for St. Vincent de Paul (who was covering the insulin cost) but yielded similar outcomes to the basal/bolus therapy.

References:

- Business Insider. Novo Nordisk and CVS offer 25 per vial insulin.

- Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2020: Diabetes. Washington, D.C.: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2014.

Over-the Counter (OTC) Insulins

The OTC insulins included are the older generation of insulin (R, N, 70/30 Mix, 75/25 Mix.) These are available without a prescription for as low as $25 for a 10 ml vial. Some Charitable Pharmacies have been able to work with suppliers to purchase OTC insulins in a limited quantity for patients.

The OTC insulins have a dissimilar action profile than prescribed insulins. However, as shown in the CINCI study, the different profile does not indicate a lower quality.

Though a prescription may not be required, ensure providers know what insulin their patients are using. Patients converting from a basal/bolus regimen to the older insulins require education as to insulin timing, mixing and storage.

Low-cost Insulin Wholesale Distributors

Sterling Distributors has been providing diabetic supplies to pharmacies, nursing homes, home care agencies and other medical supply companies for ten years. Charitable Pharmacies are able to purchase Novolin 70/30 vial 10ml ( an OTC insulin) as well as diabetic supplies.

For more information on insulin, refer to the Dispensary of Hope’s Insulin & Inhaler Savings.

Diabetic Supplies

Various suppliers offer lower-cost diabetic supplies for patient purchase. ReliOn, through Walmart, offer meters, test strips, and a wide selection of other diabetic supplies. True Matrix brand meters and strips are available at many pharmacies and on-line. Patients should check expiration dates when purchasing.

Vendors such as Independence Medical, Sterling, and Bionime, among others, offer discounted pricing and “free” offers for pharmacies purchasing products.

For information on diabetic supplies, refer to the Dispensary of Hope’s Diabetic Supplies Webinar. If affiliated with a hospital or clinic, the cost of these supplies can be utilized in Community Benefit reporting.

Many pharmaceutical manufacturers offer programs for eligible patients to receive free or discounted medication. Eligibility for these programs varies significantly depending on income, residency, insurance status, diagnosis and other factors. For eligible patients these programs supply life-saving medication for up to one year, with possible re-enrollment.

Factors to consider when offering a PAP service

As a charitable pharmacy, improving medication access is of prime importance. Access to PAPs can be managed by the patient or by the pharmacy and patient cooperatively. When managed by the pharmacy with patient cooperation, additional staff will be necessary for enrollment and follow-up. The staff does not necessarily need to be pharmacy trained as a technician, though cross-training is helpful and clear role delineation must be maintained if PAP staff is not pharmacy trained. Non-technician position possibilities include an enrollment specialist, social worker, or pharmacy navigator.

| Factor | Record Keeping – Patient | Record Keeping – Pharmacy |

| Staff |

|

|

| Staff time |

|

|

| Clinical Considerations |

|

Assures:

Trackable software available for refills, metrics Ensures

|

PAP Software Options

Software options vary depending on whether the program is patient or pharmacy managed. Programs such as Needy Meds and Partnership for Prescription Assistance link manufacturer PAP sites and applications. If a PAP program exists for a specific medication, the application is printed, completed, then mailed or faxed directly to the manufacturer. Patient specific data is not stored with these sites so copies must be retained either by the patient or, if managed this way by the pharmacy.

Additional software options exist when PAP programs managed by the pharmacy. Spreadsheets can be developed to track patients, enrollment, documents missing, refills, etc. RxAssistPlus offers a web-based software that allows for patient enrollment, PAP application fill based on enrollment information, refill and new application report notifications, and privacy compliant data storage. Completed applications are printed for signatures (patient and provider) then faxed, scanned or mailed to manufacturer. Programs such as RxAssistPlus provide record keeping and reports, and can be utilized for extensive metrics including but not limited to patient demographics, location, referral site, dollar value of applications processed, PAP meds dispensed, FPL, and clinical interventions. Experience with Word Access helps when creating specialized reports, but the reports are built by the software provider. Comparison of patient assistance program software, though dated, offers key points when reviewing software options including features of programs, logistic information, support and training, and program costs.

Steps for Processing PAPs

- Initial Medication Supply

As PAPs require shipment, the first step is providing medication until the shipment arrives. Manufacturer or discount coupons, product samples, or a therapeutic interchange may fill the gap. Some manufacturers offer coupons that provide medication for up to one year for eligible patients. This option eliminates shipping and provides immediate dispensing – a win-win for patient and pharmacy. Providers who carry samples (e.g. cardiologists, pulmonologists, etc.) may be willing to donate directly to a charitable pharmacy even if the patient is not part of their practice. (See Direct Donations).

- Eligibility

Each manufacturer has individual qualifications. Variables include:

-

- Residency requirements and documentation,

- Social Security or Tax ID number

- Income requirements, documentation, and processes (some companies do a soft credit check for initial enrollment),

- Insurance eligibility status,

- Age or diagnosis restrictions.

Therapeutic Interchange may allow patients to be eligible for a similar product when not qualified for the product prescribed.

See Eligibility for general details and documentation.

TIP: HOPE Dispensary adapted a patient specific section to record clinical interventions and associated potential dollar values. Metrics are then shared with stakeholders and funders, documenting services provided beyond med access.

- Enrollment

Patient signature (some allow caregiver, spouse, parent or guardian), As with eligibility, applications and documentation vary with manufacturers. Attention to detail is paramount in reviewing each application to ensure all signatures and documentation is complete and provided prior to submission. Application variables include:

-

- Provider signature – ensure matches provider used on application; hospital residents may lack credentials (state license, DEA number),

- Signatures to be original versus faxed,

- Acceptable photo identification, residency and income documentation,

- Original prescription versus application becomes prescription.

When providing this service at the charitable pharmacy, create guidelines and deadlines for patients and providers to provide documents and signatures. A reasonable guideline is two follow-up phone calls or requests within a four to six- week period. Document follow-up. Software is helpful for documentation and scheduling.

Once all application signatures and documents are procured, submit to manufacturer. Some require original documents/signatures necessitating mailing applications. Others accept faxes or allow scanning to a website. If a reply is not received, follow-up with manufacturer probably ten days after submission to confirm receipt of application, proper documentation, and verify patient eligibility.

- Shipping and Providing to Patient

Shipping from the manufacturer directly to the patient is convenient for the patient but may not be best practice. Although the medication has already been dispensed from the manufacturer to the patient it may not be labeled in compliance with state laws. As clinical pharmacists, we know that a state-approved label should be attached to container(s). Some manufacturers do this; others send just a packing slip and medication information sheet. When servicing a patient with PAP medication, ensure the product is properly labeled with accurate directions (not “as directed”) patient is counseled and any questions are answered. Dispensing from the pharmacy provides opportunity for both proper labeling of prescription vials and patient counseling.

| Patient | Pharmacy | |

| Prescriptions mailed to Patient | ● Saves patient trip to pick-up prescription

● Frequent changes in patient address and contact information may delay delivery ● Patient must call pharmacy for counselling or questions |

● Requires follow-up with patient to confirm delivery and questions or counselling

● Proper prescription label may be missing ● Metrics and trackability not always available |

| Prescriptions mailed to Pharmacy | ● Patient required to pick-up and sign for prescription

● Patient receives properly labeled Rx and has opportunity for counselling and questions |

● Ensure delivery of medication and patient receipt

● Follow-up for delayed delivery ● Ensure patient pick-up ● Verify proper labeling, patient education ● Obtain metrics ● Follow-up for meds not picked up ● Delivery challenges from manufacturer if pharmacy has limited hours, especially for refrigerated items |

For PAP meds picked-up at the pharmacy, guidelines are helpful.

- Call patient for medication pick-up

- Document call: spoke with patient or name of other person, left voicemail, phone number not accurate, no voicemail

- Limit number of documented phone calls or attempts (e.g. 2 attempts/30 days or less)

- At pick-up, remind patient to call for refill between 21 and 30 days prior to needed to allow time for contacting manufacturer, shipping, and obtaining a new prescription if this is the last refill.

- If patient no longer needs, would they be willing to donate to the charitable pharmacy for use by another patient? Document on packing slip and in other records with reason not given to patient.

- If patient does not pick-up within set guidelines, document as above.

- Refills

When a patient calls the pharmacy or is contacted for a refill, check for possible changes in eligibility, contact information, provider, and directions. Contact the provider to verify any changes in directions. Contact the manufacturer and relay any changes (may require new prescription for direction changes.)

Follow-up phone calls may be made to verify patient’s need for refill, usually 30 days prior to next fill. As well as being proactive, this is an opportunity to check adherence.

Document all communications with patients, providers and manufacturers.

- PAP Medication Destruction

Product dispensed as PAP from a manufacturer cannot be returned to another vendor or wholesaler for destruction. Destroy beyond use meds as per pharmacy policy. See: Medication Destruction and Standard Operating Procedures

- PAP Metrics

Measures used to evaluate a PAP program can include:

- Number and dollar value of PAPs processed (this quantifies time spent processing whether patient is not eligible, not all documentation is returned, or med is not picked-up

- Number and dollar value of PAPs dispensed (this includes new and refilled PAPs)

- Manufacturer and/or product or therapeutic class of PAPs

A manufacturer bulk replacement program or PAP allows the pharmacy to maintain a segregated bulk supply of product(s) available for immediate dispensing. The program is largely governed by individual contracts with specific manufacturers. Contract with manufacturer will determine patient eligibility requirements.

From a patient standpoint, the shipping time is eliminated when product is in stock at the pharmacy. On the pharmacy side, the pharmacy, rather than the manufacturer, accepts responsibility for verifying patient eligibility. Policies approved by the manufacturer include patient eligibility, acceptable forms of identification and income documentation, product receipt, storage, recall and destruction, and adverse event reporting. (See PAP policies) Patient and product dispensed information are usually reported monthly. Audits are annually, usually with one to two months preparation time to collect data for the auditor.

Though time-consuming to manage, a bulk replacement program may be a valuable source of branded medication for charity patients, filling therapeutic gaps not available with generic meds.

Helpful tips for incorporating a bulk replacement program:

- Record keeping and documentation are paramount

- Trained staff following manufacturer-accepted policies and processes make reporting and auditing easier

- Product labeling and dispensing are the same as other prescriptions from the pharmacy

- Add the manufacturer as a third party in pharmacy software for reports

- Adapt pharmacy prescription software to provide other information needed for monthly reports, including provider state license number and patient FPL

- Segregate prescription pick-up or use other designation to ensure collection of all necessary signatures for monthly reporting and audits

- Add alerts in pharmacy software and on prescription pick-up label for communicating with the patient about missing documentation or in need of renewing for next fill

- Tag and store charts for patients utilizing the bulk program separately, reducing time tracking charts for eligibility documentation

- Use well-trained students and/or volunteers in audit preparation.

The Drug Supply Chain Security Act (DSCSA) tracks medications from the manufacture to the patient. This feature is a safety feature to protect patients from counterfeit medications entering into the supply chain. Currently there is no exemption for sample drug donation programs. A Donation Tracking form or software record may be used for direct donations. Both the pharmacy and the donor retain copies of the transaction.

Required information includes:

- Donor and contact information

- Pharmacy or recipient contact information

- Date of donation

- Drug name, strength, quantity in package(s), lot number, NDCif available, beyond use date (expiration) and quantity of packages

Bulk repackaging (e.g. converting bottle of 1000 to 90s, etc.) also falls under the DSCSA. Bulk repackage medications (sample meds may not be eligible for repackaging) and labeling requirements may be affected by state regulations:

Med name/ Strength/ Quantity in Package

NDC

Lot #

Beyond Use Date (Max. 1 year from packaging)

Beyond Use Date is the actual beyond use date to a maximum of 1 year from packaging. See Example of Bulk Repackaging record.

Medication that is beyond the use date (expired) or has been stored such that the beyond-use date has shortened (Example: refrigerated product left at room temperature) must be destroyed appropriately.

Medication should be destroyed per pharmacy policy. A log is maintained regarding all med destruction in compliance with the EPA, DSCSA, and your destruction vendor. The medication destruction log should include:

- Date of destruction or placing in Regulated Medical Waste Bin

- Medication name, strength and dosage form

- Lot number

- Expiration date (from container; may add note if different due to storage conditions)

- Quantity destroyed (units not containers) Example: Tablets, milliliters, grams, etc.

Remove external packaging as described in Figure 3 (below) to decrease weight and destroy only medication waste. Remove patient identifying information from the packaging by removing patient labels and shredding them or covering with stickers such as an Identi-Hide sticker. A de-blister machine is a time saver for removing tablets and capsules from blister packaging.

Hazardous Products

Controlled Substances and products considered hazardous (Hazmat) or p-waste such as oncology medications, warfarin, estrogen and progestin products, finasteride, lindane, nicotine, and nitroglycerin may require segregation for destruction. See CDC Antineoplastics and Healthcare Environmental Resource Center for current listings.

- Segregation may be required in a red bag or container or container provided by the destruction

- These products, unlike regular waste, require the destruction of the empty container, lid, cotton, seal, etc. (all packaging that has touched the product.)

- Wear gloves and work in a well-ventilated area or wear a face mask.

When storing and preparing meds for destruction follow guidelines provided by destruction vendor. See Figure 3 (below)for general guidelines. Vendors may require separation of control substances, hazmat, aerosols and other items.

| Where? | How to destroy | |

| Bulk Containers | Return to vendor/wholesaler when possible | |

| Bulk Containers

NOT eligible for return |

Regulated Medical Waste bin | Dispose of paper packaging and container in regular trash |

| Oral Samples | Regulated Medical Waste bin | Dispose of paper packaging and container in regular trash |

| Inhalers | Regulated Medical Waste bin or separated as per vendor requirements | Dispose paper packaging and removable plastic mouth piece in regular trash. Discard only inhaler in Regulated Medical Waste Bin or as per vendor |

| Injectables:

Pens, Vials, Ampules, etc. |

Regulated Medical Waste bin | Dispose of paper packaging and plastic caps in regular trash.

Do NOT open container to empty. Discard with container or vial intact. Discard only medication in container in Regulated Medical Waste Bin. |

| Oncology/ Hazmat

Bulk Containers |

Return to vendor/wholesaler when possible | |

| Oncology/Hazmat

Samples, empty bulk containers |

Regulated Medical Waste bin

Or Hazmat Waste bin |

Samples, empty containers including lids, cotton, etc. discard in Regulated Medical Waste bin or as per vendor

Wear protective clothing |

|

Other |

Regulated medical waste bin | Remove paper packaging.

Discard with container or vial intact. |

Adapted from HOPE Dispensary of Greater Bridgeport

Final Incineration

Incinerating medications that are beyond use/expired may be completed economically by collaborating with law enforcement departments and manufacturing companies such as steel mills. In some states or communities, the DEA or law enforcement agency will permit charitable pharmacies to drop expired medications at the Drug Take-Back Days or Drop of Sites. It is also possible that a law enforcement agency will share a “burn” at a manufacturer’s furnace when they are burning guns and other evidence. The law enforcement and security staff at the incineration company will coordinate the burn. The companies may work directly with the charitable pharmacy to permit them to have their own burn, with or without charge.

Reference: https://www.elastec.com/products/portable-incinerators/smartash/ Accessed 4.21.18

There is usually not a charge for the service when combined with law enforcement; however, the charitable pharmacy may have an expense of renting a vehicle if there is not access or pharmacy ownership of a van or truck. The cost is well worth it. A licensed pharmacist from the charitable pharmacy will accompany the medications to the furnace area and will observe the medications being thrown into the furnace. The pharmacist will wait the brief period of time it takes for the drugs to be destroyed. The company’s security department will give the pharmacy guidance on protocols for participating in a burn and clothing requirements.

Get access to the full playbook

Get instant access to the full playbook, with more than 150 pages of valuable guidance, case studies and resources to help you develop your charitable pharmacy.